In a surprising announcement that reverberated through the tech community, Microsoft’s former CEO, Steve Ballmer, hinted at the possibility of extending the lifespan of Windows XP for sub-notebook users. This revelation has not only stirred curiosity among seasoned tech enthusiasts but has also reignited discourse about the durability and relevance of legacy software in the fast-evolving landscape of computing.

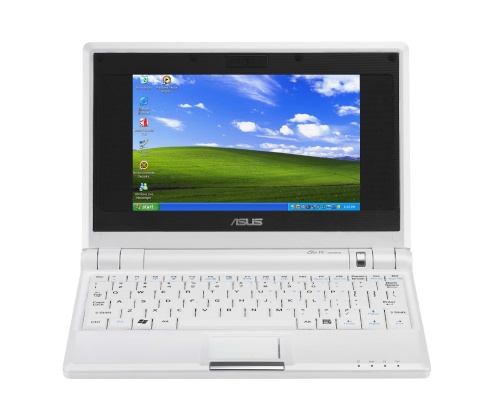

Since its introduction in 2001, Windows XP has remained a stalwart operating system, renowned for its user-friendly interface and robust performance. Despite its age, XP boasts a dedicated user base, particularly among those utilizing sub-notebooks—compact, lightweight laptops designed for portability and basic functionality. As newer iterations of Windows are rolled out, the steadfast loyalty of XP users raises provocative questions about the nature of technological adoption and obsolescence.

Ballmer’s commentary suggests that Microsoft is acutely aware of its diverse clientele; some users are not ready—or able—to embrace the complexities presented by modern operating systems. The enduring popularity of Windows XP may not merely be due to nostalgia; rather, it stems from a pragmatic understanding of its reliability in fulfilling essential computing tasks. It operates efficiently on hardware with limited processing power, allowing users to engage with technology without the burdensome requirements of more contemporary software.

This fascination with XP can be seen as symptomatic of a broader trend within the technology sector—the tug-of-war between innovation and user satisfaction. In a world where software is often designed with cutting-edge features that may overwhelm the average user, XP stands as a testament to simplicity and functionality. The prospect of its continued support is intriguing, as it can be interpreted as a recognition of users’ diverse needs and an affirmation that not all technology must be cutting-edge to be effective.

The implications of Ballmer’s remarks extend beyond mere functionality; they invite contemplation about the responsibilities of tech giants. Should companies prioritize the relationship with their users, allowing for modifications to traditional lifecycles? In the case of Windows XP, such a decision may not merely be a business maneuver but a strategic acknowledgment of the realities faced by a segment of the computing population that relies on established technologies to navigate their daily lives.

Furthermore, this discussion opens avenues for examining the economic ramifications of decommissioning older systems. For many small businesses and individual users, the cost associated with upgrading to contemporary operating systems, often accompanied by new hardware, can be prohibitive. Thus, by considering the retention of Windows XP, Microsoft may very well be addressing a significant economic concern, one that resonates with consumers and businesses alike.

In conclusion, the conversation about the extension of Windows XP’s lifespan speaks volumes about user loyalty, technological evolution, and the ethical obligations of tech corporations. As the digital age continues to advance, such contemplations remind stakeholders of the importance of inclusivity in innovation, ensuring that the technological landscape remains accessible to all.