Grading systems can vary significantly across educational institutions. Understanding a specific grade, like 20 out of 32, requires not only comprehension of numerical figures but also an appreciation of what they signify in a broader academic context. In this article, we will dissect what a score of 20 out of 32 entails, examining its implications, context, and the societal perceptions tied to such grades. We will also delve into the psychological and practical ramifications of grading on both students and educators.

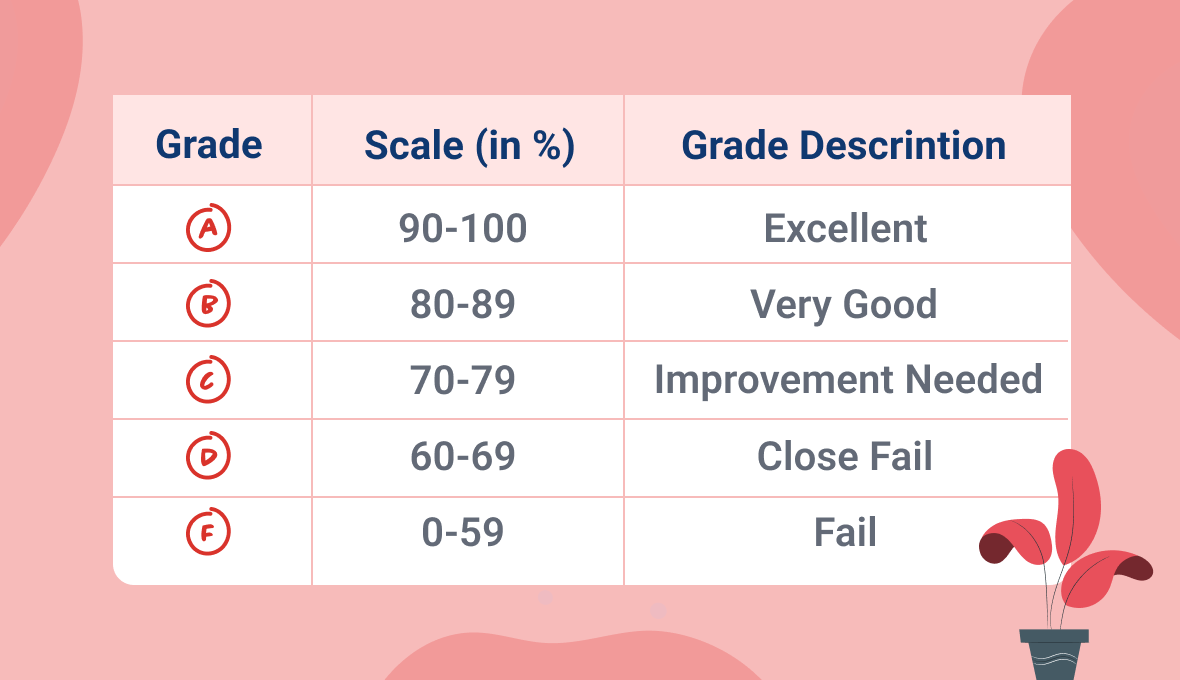

First and foremost, let’s evaluate the basics of the grading system. A score of 20 out of 32 reflects a performance that can be mathematically translated into a percentage. By dividing 20 by 32 and multiplying the result by 100, one obtains a numerical score of 62.5%. In many grading systems, this falls within a range that might be considered acceptable or average, typically denoting a passing grade, albeit one that is closely teetering on the boundary of mediocrity.

To contextualize this numerical expression, consider how different institutions interpret grades. Some academic entities maintain a more forgiving approach, viewing 62.5% as an indication of sufficient understanding. Others may adopt a more stringent perspective, labeling such a grade as lackluster, which can influence a student’s self-perception and motivation. This subjective interpretation complicates straightforward numerical evaluations and opens the door to conversations about standards, fairness, and equity in assessment.

Furthermore, the nuance of grading is accentuated when one examines the subject matter at hand. For instance, a student may achieve a score of 20 out of 32 in mathematics, a discipline often regarded as critical for analytical skills. Conversely, a similar score in a humanities subject, where subjectivity plays a larger role, might evoke a different reaction. Thus, understanding the specific discipline and the weight each course carries within an overall curriculum becomes imperative in interpreting grades accurately.

Moreover, it is essential to address the psychological impact of grades on students. The pressure to achieve high scores can lead to anxiety and stress. A grade such as 20 out of 32, particularly if perceived as unsatisfactory, can provoke feelings of inadequacy and self-doubt among students. This reinforces the need for educators to provide constructive feedback alongside numerical grades. It’s vital that students comprehend where they fell short and how they can improve, transforming a simple grade into a roadmap for growth.

Additionally, educators themselves experience a unique strain from the grading system. Teachers strive to find balance; they must fairly evaluate students’ performance while also fostering an environment conducive to learning. A mere numerical score can oversimplify a student’s engagement or effort. Thus, the role of qualitative assessments, such as participation, effort, and creativity, becomes increasingly relevant in offering a holistic view of a student’s capabilities, encouraging them beyond rigid boundaries of traditional grading.

Furthermore, understanding grading extends into societal implications. Grades can influence future opportunities such as college admissions, scholarships, and job applications. A score of 20 out of 32, while passing, may not stand out in a highly competitive arena. This raises larger discussions about educational equity and systemic biases. Are students from underprivileged backgrounds at a disadvantage when they receive such grades due to varying access to resources and support? It is a critical conversation that must not be overlooked. The grading system’s inherent inequalities need to be examined, giving room for discussions about meritocracy and privilege.

Another crucial aspect of grading systems is the evolution taking place within educational paradigms. Many institutions are moving towards standards-based grading systems that provide a more nuanced picture of a student’s understanding. Instead of rigid letter grades or percentages, they may focus on mastery of concepts. This shift could alleviate some pressure from students, allowing them to focus on learning rather than the numerical score itself. In this light, a score of 20 out of 32 could potentially lead to discussions on specific skills to enhance, rather than simply defining a student’s worth through a traditional lens.

In conclusion, comprehending a grade, particularly one like 20 out of 32, transcends simple arithmetic. It encompasses a tapestry of educational philosophies, psychological interpretations, and societal implications. Educators and students alike must foster a dialogue surrounding grades, recognizing their limitations while striving for a more holistic understanding of performance and growth. Grades should serve not just as indicators of past knowledge but as opportunities for future learning. As society continues to evolve, so too should the methodologies that define academic success.