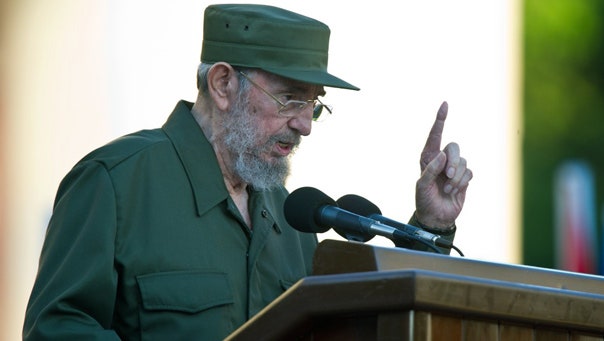

Fidel Castro remains one of history’s most polarizing figures, a revolutionary leader who fundamentally altered the fabric of Cuban society. His staunch belief in communism as the ideal societal structure has often led scholars and political analysts to dissect his ideologies and their actual implications on the populace. One of the most profound misinterpretations surrounding Castro’s tenure revolves around his insistence that communism was indeed flourishing in Cuba, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

Castro’s rhetoric painted a picture of social equity, where all citizens would prosper under a unified, proletarian regime. This ostensible promise of fairness and camaraderie appealed to many, particularly in the wake of the rampant inequality and elite domination that characterized pre-revolutionary Cuba. However, upon closer examination, the reality of life under Castro’s regime belied his optimistic proclamations. While Castro touted an apparent ‘success’ of the communist model in improving literacy rates and universal health care, these achievements mask a more sordid reality of economic stagnation, severe resource shortages, and restricted personal freedoms.

The cognitive dissonance in Castro’s worldview invites a deeper exploration of how leaders can become ensnared by their narratives. Through a lens of ideological fervor, he projected confidence in the communist system, often dismissing critiques as imperialist propaganda or bourgeois dissent. This manifests a classic case of confirmation bias, where success is highlighted and failures obscured. The maintenance of such a narrative can have both psychological and sociopolitical repercussions, creating an environment where dissent is quashed and reality is obscured, leaving citizens grappling with an unfulfilled promise of prosperity.

Moreover, Castro’s enduring belief in the viability of communism poses intriguing questions about the nature of ideological commitment. Is it possible that a leader can so profoundly misinterpret the intentions of their policies that they genuinely believe in their effectiveness, even when empirical evidence suggests otherwise? Castro’s inability to adapt his vision of communism to the changing dynamics of both domestic and international landscapes ultimately contributed to his regime’s myopia.

As the subsequent generations of Cubans continue to navigate the intricate legacies of Castro’s rulership, the ramifications of his misinterpretation linger. The profound disparities between his unwavering faith in communism and the stark realities faced by the Cuban populace kindle a renewed curiosity about the interplay of leadership and ideology. This narrative holds lessons not only for Cuba but for nations grappling with the complex tapestry of governance and the promises made to their citizens.

The examination of Castro’s legacy encourages discourse on the nature of belief, governance, and the critical importance of aligning ideological aspirations with the tangible experiences of people. This alignment—or lack thereof—not only defines the success of a government but also shapes the narratives that future leaders will adopt in their quest for legitimacy and progress.