When one thinks of wars, images of soldiers in combat gear and tanks rolling across battlefields often come to mind. However, the peculiar conflict between Australia and emus in 1932 serves as a vivid reminder that not all wars are fought by nations against nations or armies against armies. Instead, this bizarre chapter in Australian history illustrates the often precarious relationship humans share with nature.

In the 1930s, Australia faced a tumultuous time economically, particularly in rural areas, where the effects of the Great Depression loomed large. For many farmers, primarily in Western Australia, crop production and livestock farming served as the backbone of their livelihoods. However, this reliance on agriculture was soon complicated by an unexpected intruder: the emu.

Emus, large flightless birds native to Australia, became infamous plant eaters, causing havoc in wheat fields and other farms. With their impressive stature—standing up to six feet tall—and insatiable appetite, emus were far from benign. Farmers quickly realized that these birds not only decimated their crops but also posed a significant threat to their already precarious financial situation. This situation led to the involvement of governmental authorities, which believed that a more strategic approach was needed to tackle the emu menace.

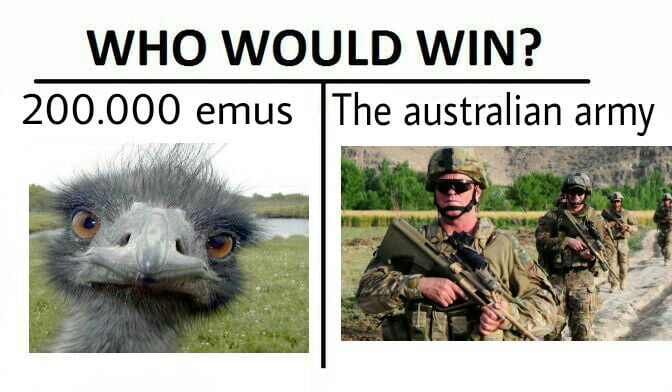

The year 1932 marks the beginning of an unconventional bout commonly referred to as the “Emu War.” The term can elicit both humor and disbelief, but the events that transpired were far from laughable for those directly affected. Armed with weaponry and strategic ambitions, the Australian government decided to intervene directly. A small battalion of soldiers was dispatched to combat the emu invasion.

Equipped with machine guns that were intended for use against human foes, the soldiers faced an unexpected challenge: emus are not only hardy but remarkably swift. They could run at speeds of up to 31 miles per hour, and their agility made them difficult targets. As audacious as it sounds, the soldiers’ failures to effectively cull the emu population soon became apparent—despite firing thousands of rounds, the number of emus killed was staggering low, not even reaching double digits in some accounts.

This inability to achieve a decisive victory led to mounting frustrations, not just among the soldiers but also among the farmers who were counting on a swift resolution. The war against the birds was compounded by logistical issues, as emus exhibited a form of guerrilla warfare. They often scattered in all directions, confusing the soldiers and thwarting their attempts at elimination. Some even cleverly learned to hide from the soldiers, sidestepping the battle altogether.

As the months of 1932 unfolded, it became increasingly clear that this was no straightforward conflict. The Australian government, faced with mounting public ridicule, eventually decided to withdraw military personnel. Following their retreat, emus continued to wreak havoc on the farmlands, evading human efforts to subdue them. A few hilariously ironic attempts to outsmart these birds—such as erecting fences—met with limited success. The emus, after all, were highly resourceful and the terrain was often challenging.

What culminated in an embarrassing retreat soon became a fascinating anecdote of Australian folklore. Just imagine soldiers tracking a flightless bird during what was ostensibly a “war.” The Emu War became a symbol, a tongue-in-cheek representation of the struggles that humans face whenever they attempt to impose their will on nature.

This curious episode invites an exploration not just of the comedic elements inherent in declaring war on a species, but also deeper reflections on humanity’s often tumultuous relationship with wildlife. It underscores a pivotal question: what gives humans the right to wage war on the natural world? As societies evolve, the impact humans have on the ecosystem becomes a matter of ethical consideration. The Emu War serves as a cautionary tale about the complexities of such interactions.

Furthermore, the absurdity of the Emu War has become a topic woven into modern Australian culture. Educational programs, documentaries, and satirical discussions surrounding this historical misadventure continue to incite laughter and introspection alike. At its core, this conflict underscores the importance of coexistence, coexistence that doesn’t require warfare but rather dialogue and understanding.

In today’s world, where biodiversity is increasingly threatened, the lessons of the Emu War resonate even louder. The need for ecological conservation and respect for wildlife has never been greater. Engaging in warfare against nature is simply not a sustainable approach; the history lesson from 1932 serves to remind modern society of that. Wild animals, like emus, play crucial roles in their ecosystems, and their existence often balances the environments that humans benefit from.

Ultimately, the Emu War stands as both a humorous episode and a sobering contemplation on the dynamics of power between humans and nature. The ensuing conflict exemplifies that, sometimes, it is better to strive for harmony rather than conquest. It augments the notion that while humans may have technological advancements to assert dominance, nature remains an indomitable force—one that often resists our attempts to control it. Thus, as society grapples with contemporary environmental challenges, the story of the Emu War urges us to reflect upon our obligations to the world around us. Instead of waging war, we ought to aspire to engage in a relationship characterized by respect and understanding.