In an era where access to information is paramount and libraries serve as bastions of knowledge, the notion of criminal repercussions for overdue books seems anachronistic. Yet, bizarre instances of individuals being incarcerated due to unpaid library fines or unreturned books have emerged from various corners of the United States, generating intrigue and, at times, ire among the public. The phenomenon raises pivotal questions about justice, societal values, and a systemic approach to law enforcement.

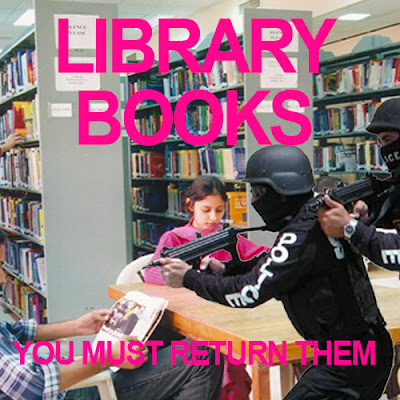

The case of a Texas woman, for instance, highlights the extraordinary lengths to which police and libraries may go when confronted with persistent offenders. In this case, the individual faced jail time not just for the simple act of not returning borrowed books, but for accumulated fines that overshadowed the original value of the materials in question. This scenario invokes a plethora of discussions surrounding the efficacy and ethics of penalizing citizens for relatively minor infractions within the justice system.

Libraries, once considered havens of learning and community engagement, find themselves navigating the treacherous waters of budget cuts and dwindling resources. As a response, some have adopted stricter policies regarding overdue materials. Gone are the days of goodwill and leniency; libraries now often resort to fines as a means to recoup losses, a practice that increasingly intersects with legal action. However, the decision to press charges against patrons raises ethical dilemmas about targeting vulnerable populations, such as low-income individuals who may be unable to afford fines.

The legal ramifications of overdue books can vary significantly from state to state. In some jurisdictions, fines accumulate until they reach a threshold that permits collection agencies to intervene, leading not only to further penalties but also potential criminal constraints. Meanwhile, other regions have begun exploring more humane alternatives such as community service or “forgiveness” days, where overdue notices are absolved in exchange for participation in community programs.

Critics argue that penalizing people for overdue library materials betrays the educational ethos of libraries. They contend that resources should facilitate accessibility rather than restrict it. This sentiment is echoed in the push for decriminalization, reflecting a growing consensus that library statutes should prioritize nurturing literacy and accessibility rather than punitive measures.

Moreover, the 21st-century digital landscape complicates this narrative. With e-books and digital libraries rising in prominence, the need for traditional book return policies may warrant reevaluation. If patrons can access vast reservoirs of literature online without the constraints of physical returns, many ponder if the very concept of overdue books needs restructuring altogether.

In conclusion, the phenomenon of incarceration over overdue library books is a convoluted tapestry woven from perspectives on justice, access, and societal values. As communities grapple with ensuring that library services remain equitable and accessible, the dialogue around fines and penalties will undoubtedly evolve. The overarching challenge remains: how to balance the sanctity of library resources with the imperative for a just and compassionate society.